- MathNotebook

- MathConcepts

- StudyMath

- Geometry

- Logic

- Bott periodicity

- CategoryTheory

- FieldWithOneElement

- MathDiscovery

- Math Connections

Epistemology

- m a t h 4 w i s d o m - g m a i l

- +370 607 27 665

- My work is in the Public Domain for all to share freely.

- 读物 书 影片 维基百科

Introduction E9F5FC

Questions FFFFC0

Software

Presentation in English given at a conference in Lithuanian on Comparativism, Globalization and Changes in Contemporary Discourses on Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art: Komparatyvizmas, globalizacija ir dabartinių estetikos bei meno filosofijos diskursų kaita, Lithuanian Instute of Cultural Studies, May 4, 2018.

Leonard Bernstein was an American composer and symphony conductor. In 1973, he gave six lectures at Harvard, "The Unanswered Question", which is the title of a symphony by Ives, the American composer. But for Bernstein, the unanswered question is, Whither music? Which direction will music go in? Because he lived in a time when musical tradition was very unclear.

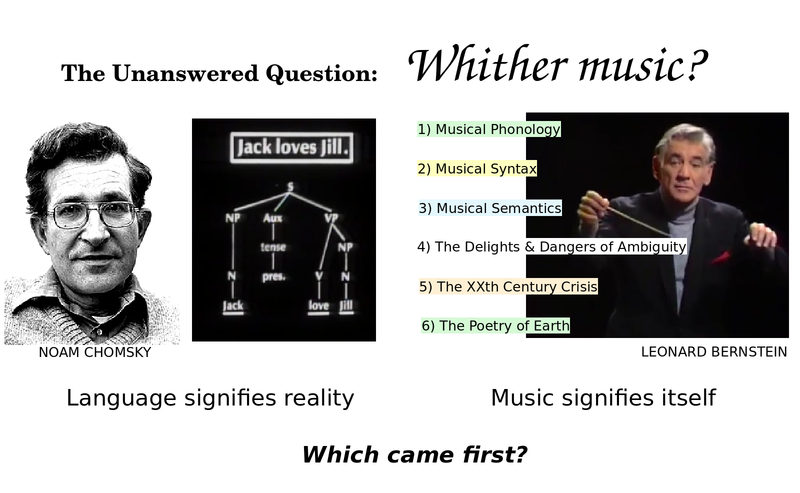

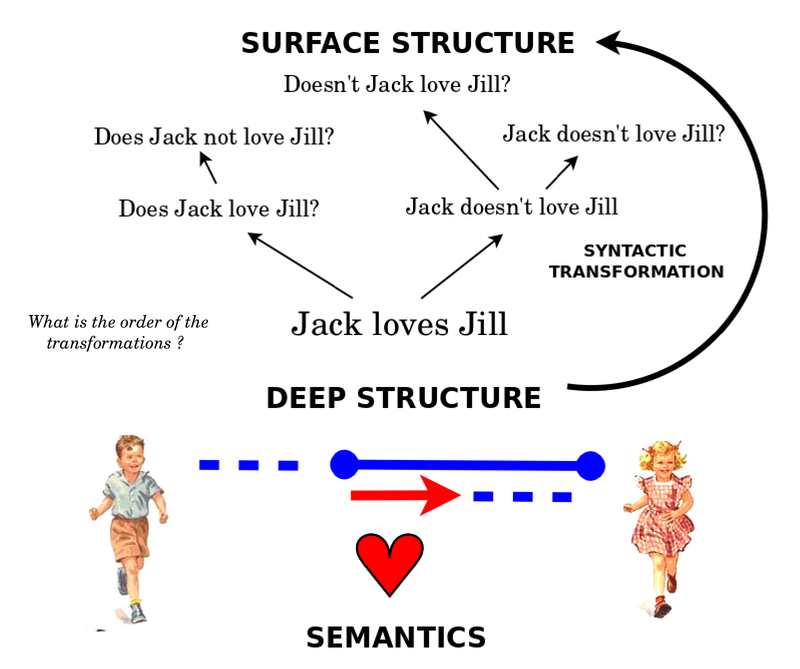

He was very intellectually thrilled by Noam Chomsky, the famous linguist. You see a diagram of a sentence, "Jack loves Jill".

Leonard Bernstein's lectures were videotaped and you can find them on You Tube. They are miraculous in that he spoke, but he also showed slides, and he also conducted an orchestra, and he also sat by a piano. I will show a couple of clips.

He was interested to apply linguistics to music. He talked about musical phonology, syntax, semantics and he led to the concept of ambiguity. He said that in the twentieth century there was a crisis of too much ambiguity. In his final lecture, "The Poetry of the Earth", he gives his solution.

This inspires a bunch of questions of my own which I wish to talk about. One question is, which came first, language or music? With language, we see it modeling something. Language is a system that is modeling reality. It signifies reality. But music is also very much a system. But it does not signify reality, it signifies itself. It maps onto its own structure.

So the question is, which is first? When you think about it logically, you can see that that's an argument that music cames first. It's much more easy for a system to learn to map itself and then from an evolutionary point of view it becomes useful for mapping the world.

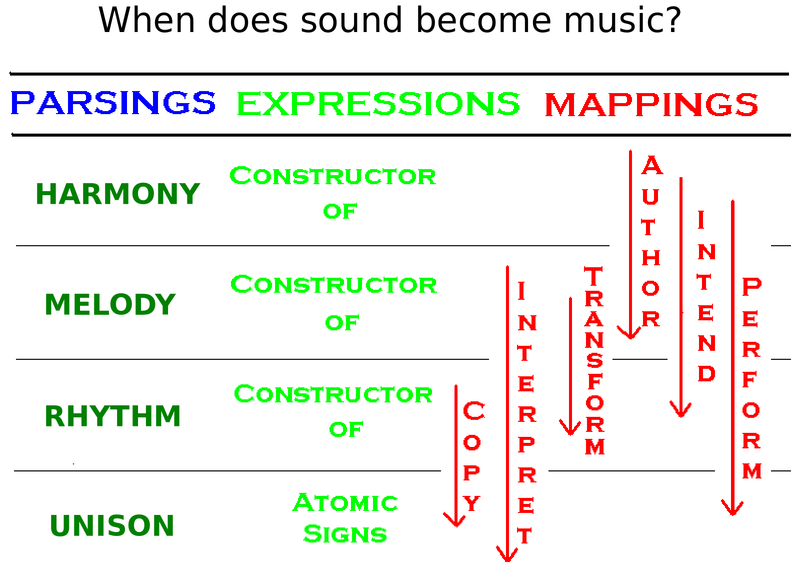

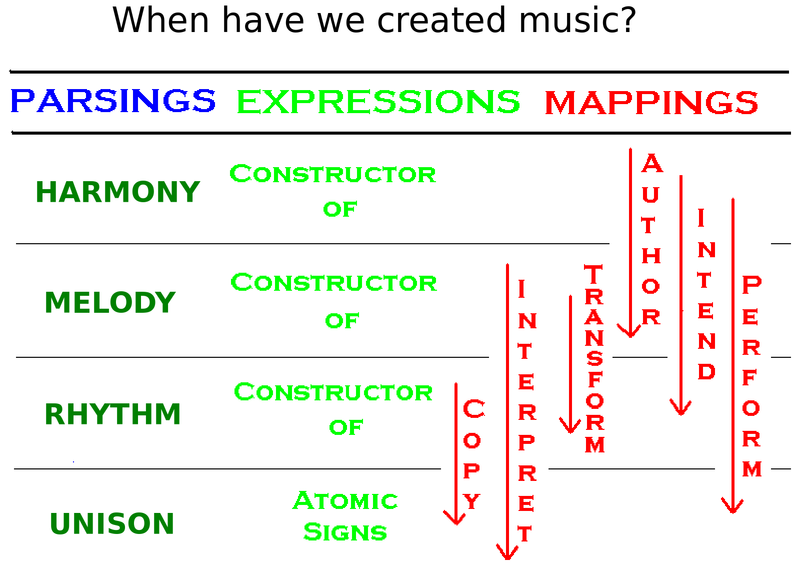

Let's look at some other questions. This is the main question of my talk. When does sound become music? These will be four levels epistemilogically, whether, what, how and why. We'll see that human beings make sound into music. And that requires unison, and it requires rhythm, and it requires melody, and it requires harmony.

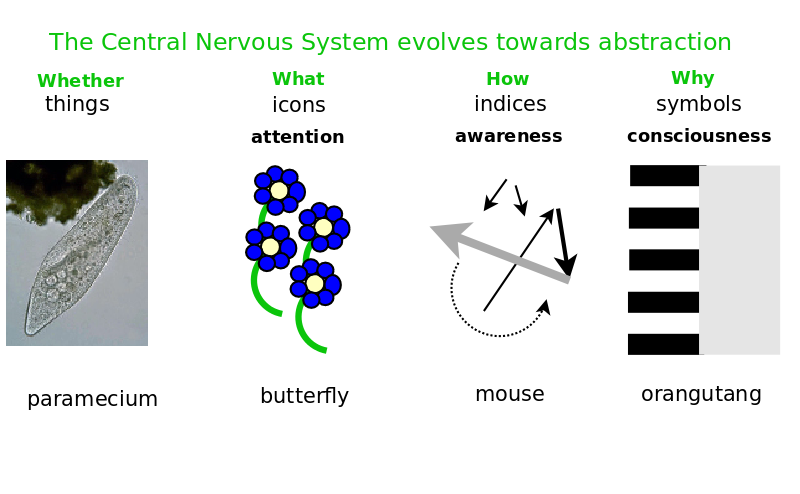

The strange thing about evolution is that it heads in a direction. The central nervous system is evolving towards abstraction. It is a very strange thing. A paramecium, a one-celled organism, touches the world directly. A butterfly doesn't live in nature. A butterfly has a nervous system and a butterfly lives in a world of flowers, of pictures. A mouse or a cat, they don't live in a world of pictures, they live in a world of arrows and indices. The mouse is able to make a model of its attention, and it's able to make a model of the cat's attention, and it's able to say, that cat is looking at me or not. An orangutang has an even more abstract world.

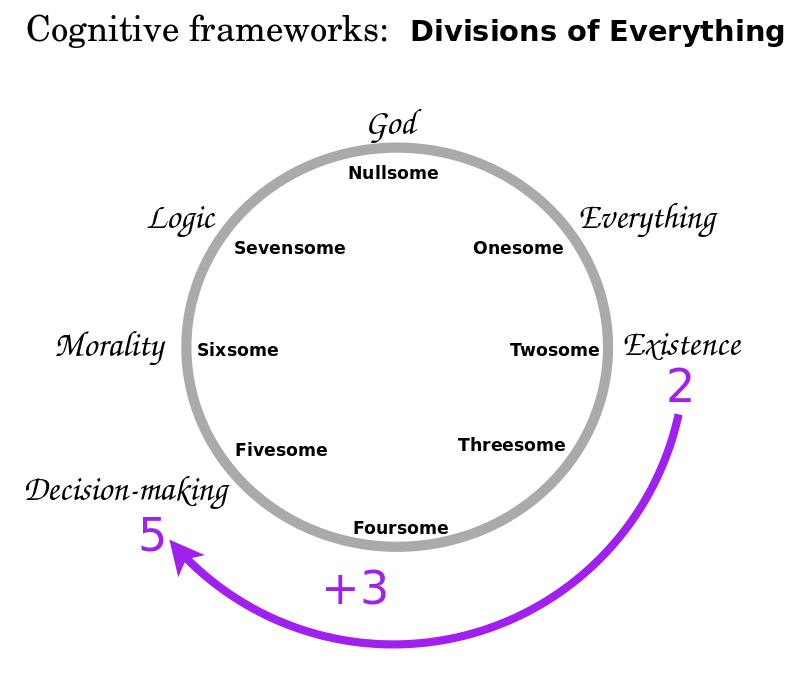

An orangutang is able to say, there is a global workspace in my mind, there is everything. And part of that workspace is maybe paying attention to this, and part of the workspace is paying attention to that. Part of the workspace is saying, maybe this chair exists or not, I have free will, and part of the workspace is saying, if it is, then it is, and it is, it's fate. An orangutang is able to reflect on issues of existence. So an orangutang can do that and Birute Galdikas says that the orangutangs go off and they, like Buddhist monks, are able to meditate. What happens to humans? If you look at these different frameworks, then whether you're an orangutang, or a great ape, or a human, we're all able to be conscious. That means we are able to choose our state of mind, whether we are stepped in, or whether we are stepped out. Like an orangutang can choose to ignore me or not. So it is conscious. And it lives in a very tight circle of these divisions.

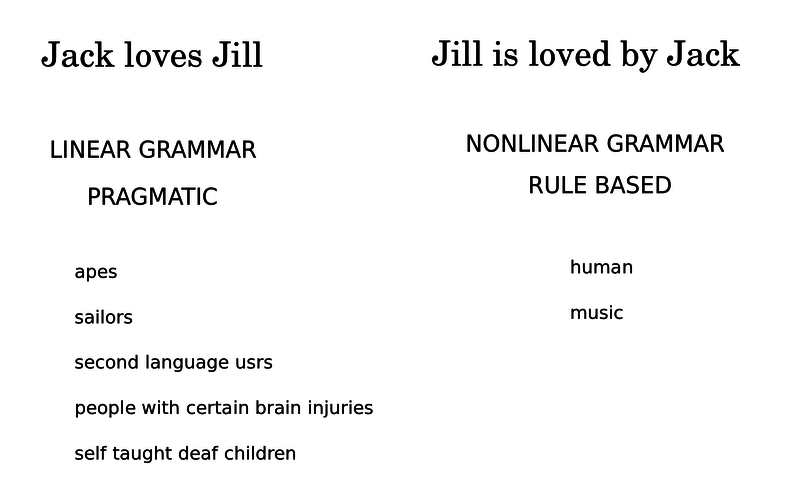

An orangutang can have linear grammar. It can have hundreds of words. It can have the words for Jack and love and Jill. It can say "Jack loves Jill" and that would be called linear grammar. From the pragmatic context you decide what Jack and Jill mean.

Apes can do that, sailors from different countries can do that with pidgin, second language users who go to another country, people with certain brain injuries can still speak this way, and deaf children, if they live with their parents, can speak with their parents in this way.

But they cannot say "Jill is loved by Jack". The word order is changed. That would cause confusion. "Jill is loved by Jack" is a nonlinear grammar. It is rule based. You have to understand which is to which. Humans can do that and music is like that.

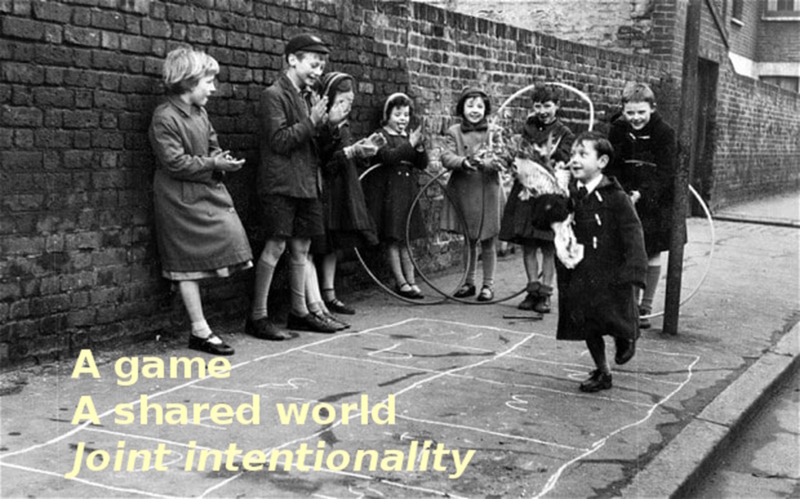

What is it that makes humans human? If you look at how you are sitting here, you are not sitting the way orangutangs are singing. See, your hands are crossed. Your hands are matched in a way. Everyone is harmonized. And these children are harmonized all with each other. It's like they are dancing.

I have drawn some lines. These lines show that they are all related.

And even if their attention is in different worlds, but still their bodies are kind of related. Their bodies are paying attention to each other unconsciously.

Let's compare this with apes. All of these chimpanzees are doing the same thing. I think they are being fed. They don't look like they are paying attention to each other. Each is in it's own world. We could not do this because this is too strange.

They have one-on-one relationships and they have very complicated politics. But each one is with another one. They are not as a group. We could take this room and have two different groups, and the one group would have its own harmony and the other group would have its other harmony.

These children in Ethiopia are singing and dancing. If you look, their attention is very different places, but their bodies are in perfect harmony. There is a beauty in the way they are standing.

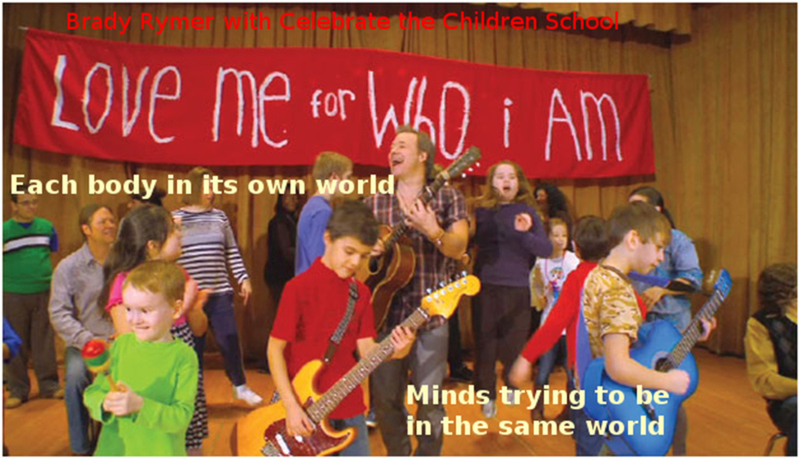

Autistic children don't have this. All of these autistic children are in their own world. We have a sixth sense just as we are seeing and hearing. It's a physical sense of synchronicity and you can lose it. It can be damaged and you will be blind. Or it can be diminished. Asperger's syndrome is something like autism but it's like being nearsighted. They don't know when to start a conversation and they don't know when to end a conversation. If they do, it's because they learn it consciously. They are the same human beings we are, but they don't have this physical faculty.

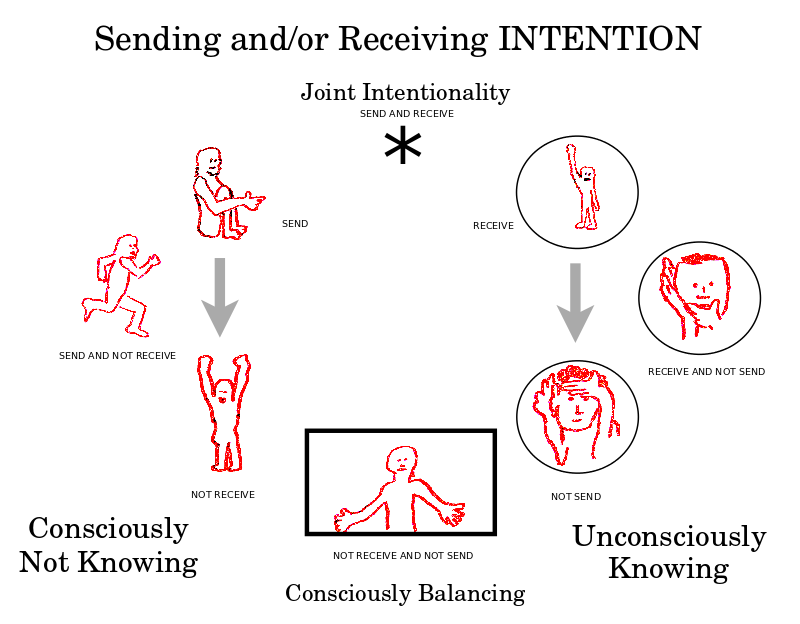

What does this physical faculty do to makes us human? It means that we can tune to each other. And if we are tuned to each other, it will mean that we can have ambiguity. It will mean that we can have two different systems. Maybe one person is talking, but maybe another person is listening. Then maybe they switch. Are they sending the signal or are they receiving the signal. So this very complicated. It's a division of everything into eight perspectives. The idea is that it collapses if you are both sending and receiving the signal.

Chomsky was looking for the universal grammar of language. He's saying that it's completely remarkable that the little two year old, three year old, four year old child is able to learn Japanese or Lithuanian or English with very bad data. People are not programming this child. They are just speaking and the child is able to figure it out. So there must be some kind of decoder in the mind, a universal grammar that allows the child to figure it out.

Leonard Bernstein felt so lost in the musical chaos of his time. He was looking for the musical grammar of music.

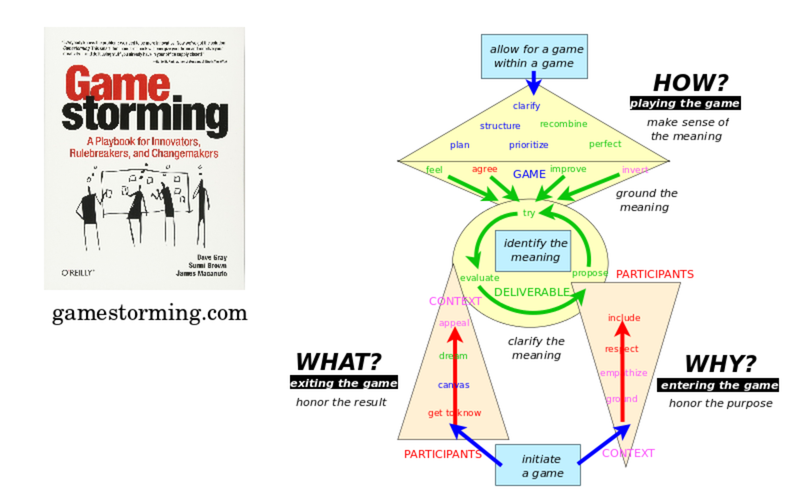

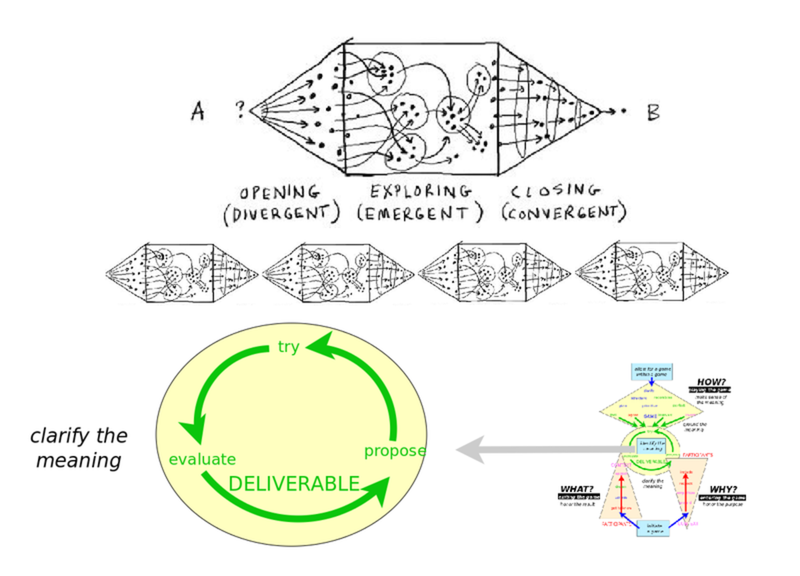

I think that I've found that grammar, but it's the grammar of games. Games are bigger than language and bigger than music. I looked at Silicon Valley innovation games. They would play games to make up products to sell to us. You have games to start the creative process. You have games to conclude the creative process. You can have a game within a game. You can have a game to get the ideas going and then to diverge, but then you can have a game to pull it all together. I can't talk about it today. But I want to talk about how we build to that structure.

I am going to sing a Lithuanian song. The beautiful thing about the videos with Leonard Bernstein is that the man has such a tremendous intuition about music that he can play with it, and know it, centuries of styles and creativity, and he can try to play with musical ideas. I don't have that. I have to be smarter. I say, let's just look at children's songs. The children's songs will explain everything. Let's sing this Lithuanian song, all together:

(Garnys, garnys turi ilgas kojas. Garnys, garnys turi ilgas kojas. Bėgčiau, bėgčiau, kad galėčiau, tokias kojas, kad turėčiau, kaip garnys. Bėgčiau, bėgčiau, kad galėčiau, tokias kojas, kad turėčiau, kaip garnys.)

The crane, the crane, has lo-o-ong legs.

The crane, the crane, has lo-o-ong legs.

Run, I'd run, I would, I would, if I could have such very long legs like the crane.

Run, I'd run, I would, I would, if I could have such very long legs like the crane.

Apes cannot do that. They cannot sing in unison. To sing together in unison is the same thing as the synchronicity and it probably came first. Birds make beautiful sounds, but birds don't sing at an octave difference. Men and women sing in different octaves, which means they tune in to the abstraction, rather than the sound itself.

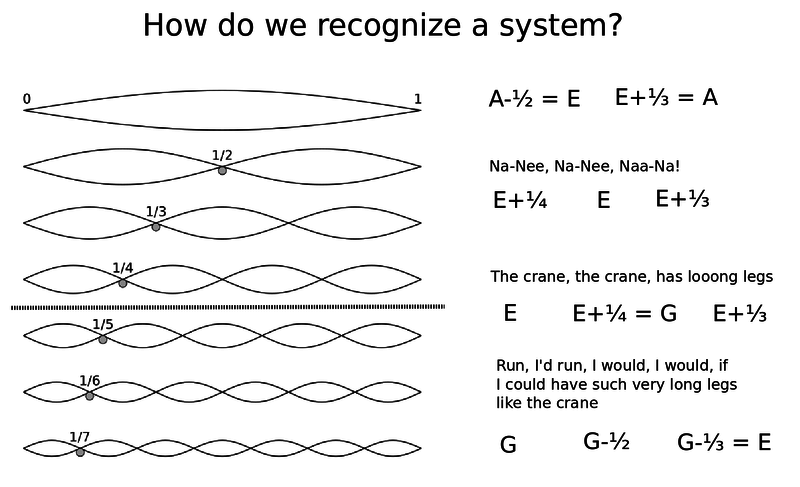

This is what Leonard Bernstein called musical phonology. The point is that you can take any sound on the spectrum and you can divide it and you will find resonance and you will have octaves. If you split the wave in half, it will be an octave difference. It has nothing to do with where you start, but it has to do with the structure. We can tune in to each other but we also have an abstract world in our minds. Apes also have this abstract world but they do not have the physical facility to be able to say, they are singing one octave, and we will sing the same one octave lower. Whereas we don't even notice that we can do this.

We can sing so that the sound waves splits in thirds, and in fourths, and in fifths.

Leonard Bernstein points out that there is a universal taunting song. "Nya-nee, nya-nee, nya-nah!" This uses the third and the fourth harmonies.

If we want to have a syntax, we need to have well defined atoms. We have to be able to create the sound together in unison. The next level is that we can have a rhythm. But that is not music yet. The next level is that we can have a melody. That is not music yet, but it's getting close. You need harmony to have music.

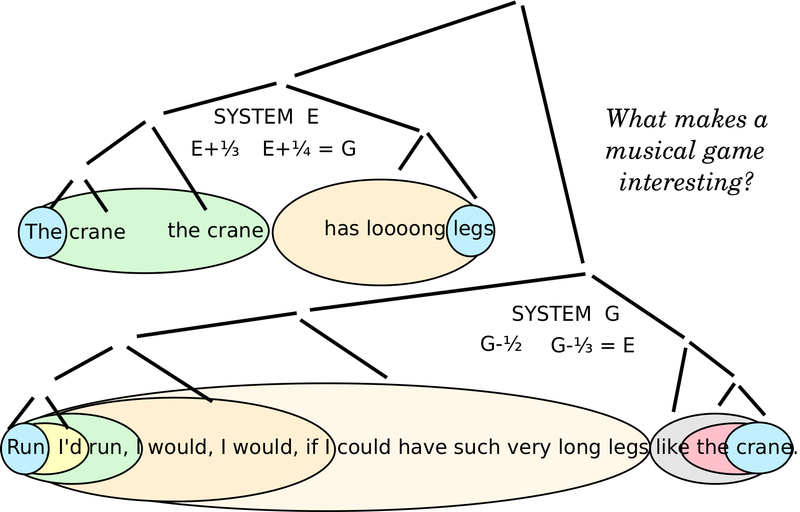

The crane, the crane, has lo-o-ong legs.

If you study it, not accordingly to the typical Western scale, but according to physics, then in the song "The Crane", you have this E sound and you will also use E + 1/4 and also use E + 1/3. Those three sounds are creating a chord, a musical system, based on E. Now E + 1/4 is the same thing as a G.

Run, I'd run, I would, I would, if I could have such very long legs like the crane.

The second half is built on G, G-1/2, G-1/3.

This is harmonic arithmetic and we do it automatically. Just to show how strange it is, I will give you a math problem. It's very important because it shows the relevance of having two systems. It's like having two cafes. I have my favorite cafe, I buy my sandwich there. It costs nine euros. Across the street it's always one-third more. But now they are having a sale today, and all of their sandwiches are one-third off, one-third less. Where should I buy my sandwich? Where is it cheaper? Many people think it's the same. But one-third more of 9 is 12, and one-third less than 12 is 8, because it's a different third. In fact, one-third of 9 is equal to one-fourth of 12. It's very confusing because we are using two different systems.

You can tell which system you are in, depending on what thirds and fourths you are using. The point is that having two systems is what makes it music. "The crane, the crane" is not music. "The crane, the crane, has lo-o-ong legs" is still not music. It becomes music at the point when you sing "Run, I'd run, I would, I would..." You need to compare two systems to have music. You need to have a dialogue.

That's what's happening with syntax. When you have two systems, then you can say the difference between "Jack loves Jill" and "Jill is loved by Jack". With music, are you in the system for "The crane, the crane..." or are you in the system for "Run, I'd run, I would, I would..." You have two different systems and you can tell.

This is Chomsky's idea and this is what Bernstein loves so much. You have semantics, which would be some direct meaning such as "Jack loves Jill". It is the deep structure. I will relate it to games.

What games do, games create a world. You enter a world by asking a question. Then you play around. And then you leave a world by getting an answer.

For example, What is Jack? That's the question. You are Jack. That's the answer.

What is Jack? That's the question. Jack loves Jill. That's the answer.

Subject - predicate. Sign and signified. I'll show a clip from Bernstein where he shows how beautifully this works. This is an example of how question and answer works with music.

Leonard Bernstein video: Call and response

You can see they are very good lectures. He saying, that's the semantics of music. He says it's a metaphor. It's a metaphor of dialogue.

We don't know what they are talking about. He's making up the words. But he's saying that music has that meaning of dialogue. It's almost like hearing people talking. You don't know what they are talking about. You can sense that something is going on.

You can become emotional about that. So what Chomsky does with this "Jack loves Jill", which is the linear structure that apes can understand, but what humans do is they can transform it. So they can take "Jack loves Jill" and they can say:

"Does Jack love Jill?" They can make it into a question.

They can make it passive. "Jill is loved by Jack."

They can make it negative. "Jack doesn't love Jill."

The crucial thing for Chomsky's theory, what he did, is that he showed that these transformations are syntactic, not semantic. He showed that they seem to have a logical order in the mind. For example, first you may negate: Jack doesn't love Jill. Then you may ask two different questions. Jack doesn't love Jill? would be one. Doesn't Jack love Jill? would be another. And they are slightly different syntactically, but the crucial thing is that, in the mind, the transformations have that definite order.

I want to show what that kind of order means for Leonard Bernstein. I will show one more clip from his video lecture.

It's exciting to watch him because he's able to imagine this type of relation. And he has the intuition that maybe we could figure it out. From a scientific point of view he's very inspiring.

I might answer his question. You have a tonic and then you play with it but you have to keep coming back and returning to some kind of tonic or some kind of message.

In this system, you have to have these four levels. When have you create music? First you have to have unison, then you can have rhythm, then you have some kind of information melody, but the crucial thing for music is that you have to have harmony, which means you have to have different harmonies. You have, say, an E system and a G-system and they are talking, and you have a dialogue between two points of view, and then you can have ambiguity. Which point of view am I in? Which system am I in? That is when it becomes interesting, and you can have layers and layers and layers of ambiguity. Of course, you can get lost if you don't have a very strong tonic. So you have to have a strong tonic, then you can wander, then you can wonder where am I? and then you have to come to a new tonic.

When we talk about epistemology these levels are the same lavels that Rasius talked about. What something is - that would be the rhythm. That is the copy and you could be making copies. How something is - the know-how - there is a model that we're making the copy from. But with nature there are two things. There is the original, obvious thing that we can all be tuned, and so we can create an abstract reality. But finally there is some kind of harmonic truthful world that the genius is coming from. There will be six types of artistic relationships between these four levels.

Each level requires a different parser. You have one parser to combine things into rhythm. Similarly, you combine sounds into words, but you need to combine words into sentences with a different parser. With computers we have different parsers for different levels of information. Music is likewise.

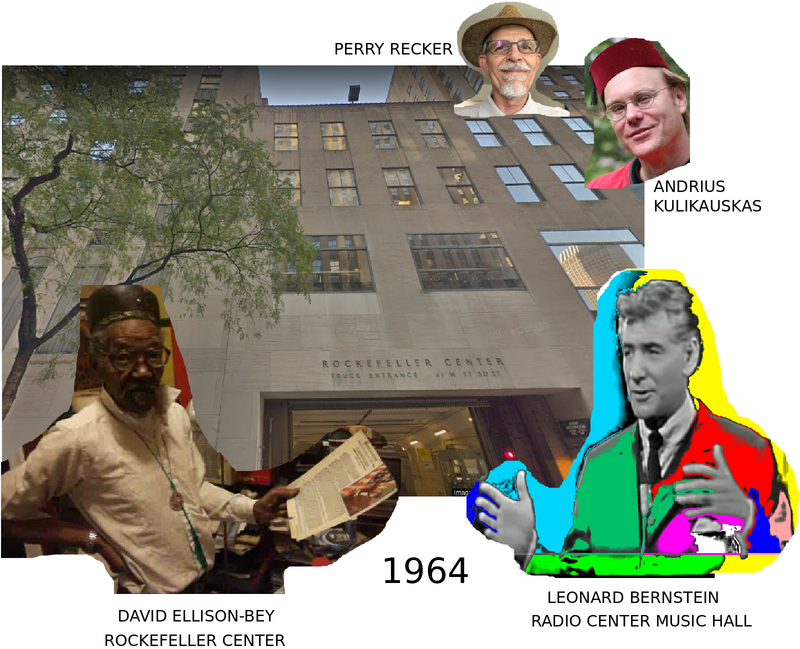

My friend David Ellison-Bey and Leonard Bernstein knew each other in 1964. Leonard Bernstein used to go outside and smoke and talk to my friend. And he would say how he is so unhappy that they make him do a certain type of music and he wants to make his own music. He would talk to this black man, and they would smoke together, and he would tell him his feelings. I just want to say that he was a very democratic person. This is a story of what music is.