Daniel Ari Friedman leads this Math 4 Wisdom study group

- Daniel Ari Friedman

- Andrius Kulikauskas

- Epistemological portraits

- Translating ontologies

- Evolution

More Links

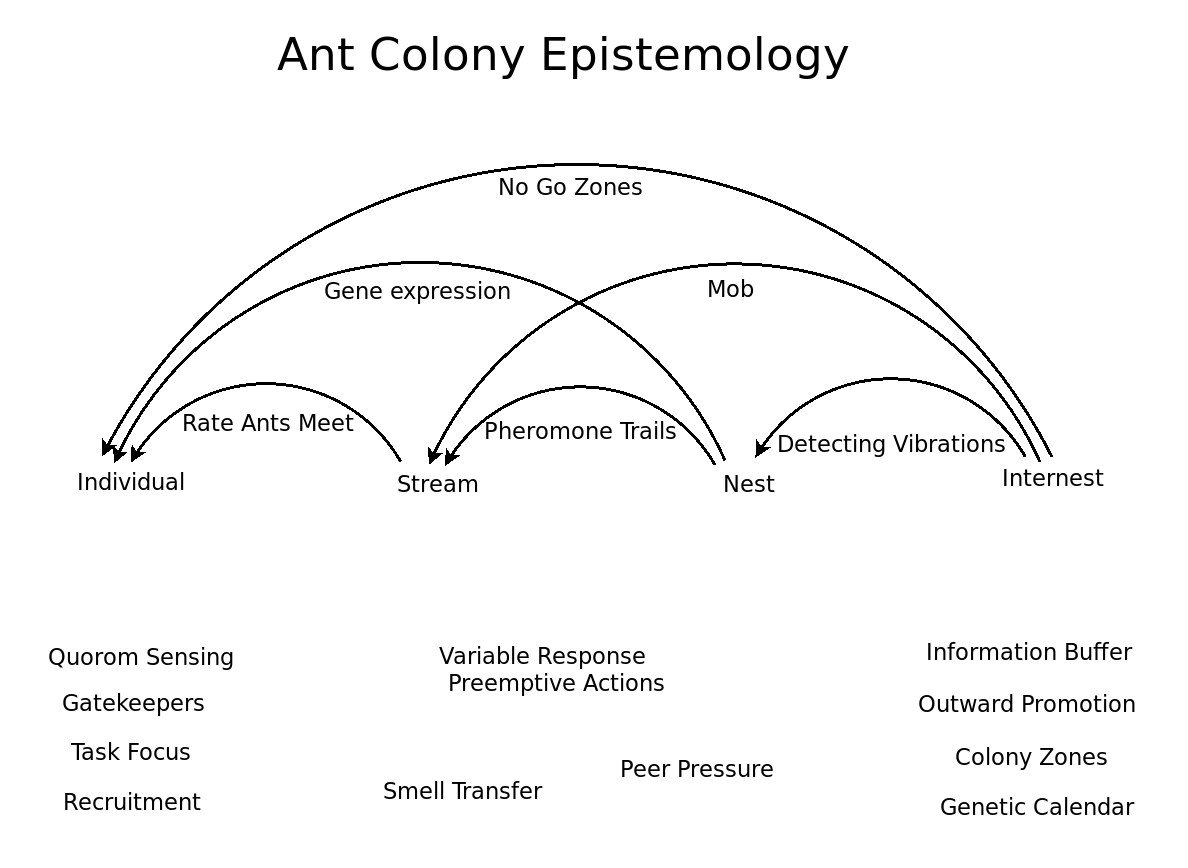

Andrius Kulikauskas: I am collecting and systematizing the ways that ant colonies figure things out, with special focus on red harvester ants, where possible.

Ant Colony Epistemology

Mind That Knows

Within random fluctuations of interactions, everything is apparently normal, and so everybody does as they've been doing. Like the butterfly that lives in world of flowers, a world of images.

Mind That Does Not Know

When there is a non-random fluctuation of interactions, for example, foraging ants are not returning, then that signifies that something odd has happened, and accordingly, behavior changes, for example, fewer ants go out. In what sense is an ant colony able to model attention in the way that a mouse or cat does?

The queen or queens live deep inside in an insular, removed semiotic world based on smells. There state is mediated by nurse ants. The nurse ants can turn from friend to foe based on the queen's smell. Smells are communicated from the queen to the outer world and vice versa through grooming. The queens and nurse ants are insular in the manner of an imperial Mandarin court, which was often run by eunuchs, concubines and wives.

Consciousness

The third mind, which balances the other two, and chooses which one to execute, is I think the nest maintainers, who alter the structure of the nest. I think they get help from the scouts and the nurses and the "do-nothing" ants.

Communal Intelligence

Changes in gene expression

- Gordon: Gene expression in ant tissues can change based on the time of day or even perhaps based on the task that an ant is doing.

Flow of ants, the rate at which ants meet.

- Gordon: Determines whether ants go out or stay in the nest.

Zones in the colony - outside ants, middle ants, inner ants.

Task allocation

- Colony adjusts which ants do which tasks and whether they do those tasks.

- There is a stream of flow from tasks for younger ants (inside) to tasks for older ants (outside).

- Caring for larvae -> nest maintainers -> patrollers -> foragers (nest maintainers can also become foragers) there are also midden keepers

- Contact with midden keepers has an ant switch to midden keeping.

Task focus

- A forager ant finds its seed and brings it to the nest and sets it down. It lets others worry about it further. It waits to be stimulated to go back to the same place and find another seed. Basically, to repeat what it just did.

Peer pressure

- Ant will take up a task that is popular.

Response to high humidity, risk of flash flood

- Ants may plug the nest entrance.

Response to new food source

- Increased number of foragers.

Response to weather (flooding)

Detecting vibrations

Nest choice

- Temnothorax move nests frequently. Ants investigate new sites, are more likely to stay in viable sites, and when enough ants assemble (based on the rate of antennal contact), scouts recruit the rest of the colony to the site.

Passage of time

- Sending out virgins to found new colonies.

- Colonies grow larger until they are 5 years old and then they are stable in size but start reproducing.

- What happens if you destroy half of a colony? Does it focus on repopulating or reproducing or both?

- Older colonies act more consistently, younger colonies are more variable, week by week.

Whether to forage

- Not worth foraging if the search time is long. Foraging costs water, which they acquire from the seeds they gather.

- Seed availability is random as they are distributed by wind and flooding.

- Patrollers are gatekeepers, they tell whether to go and which direction.

- Glass beads that smell like patrollers is enough to bring out the foragers if the glass beads are dropped at a rate of 1 bead per 10 seconds (just like the usual rate for the return of patrollers).

- Can make foragers go out sooner if the glass beads are dropped earlier.

- It seems there is a decay in stimulus on the order of 10 seconds.

- Fifty patrollers can set the direction for thousands of ants.

Where to forage

- Colony choose a particular direction for the day

- If a particular trail is blocked, then the ants will focus on a different trail, rather than try to break through the blocked trail.

- Patrollers avoid the direction of the patrollers of the neighbor. So they don't return by the trail they went out. In that way they don't mark that trail and foragers don't use it.

- Foragers follow the chemical that patrollers put down so they take the trail that the patrollers return on.

- A forager returns to the same location on successive trips. It is triggered by a returning ant but it does not care what direction the returning ant found food, but simply heads out again to where it was before. It is not recruited to a specific location.

- Fire ants have pheromone trails. The more food, the more ants lay trail, the stronger the chemical trail.

How many foragers

- Foragers go out in the direction from which come foragers returning with food.

- Foragers don't go out in the direction when foragers come back without food.

- The more food, less search time, quicker return, more foragers go out. Foragers respond quickly and sensitively to successful foragers coming back.

Search time

- Search time is a good measure of the availability of food. Ant leaves the trail and searches around for about 20 minutes, up to 20 meters from the nest. Trip duration is correlated with search time. But not correlated to the distance to the nest.

Competition with neighbors of the same species

- May fight

- May die from dessication in the heat but still be clamped to the ant it attacked.

- Probability of fighting changes day to day. May depend on climatic conditions that affect the chemicals that have been laid down. Andrius: Perhaps the chemicals encourage peaceful division of territory but they get washed away with the rains.

New colonies are not likely to survive near an established colony.

Crisis response

Downsizing?

- If all of the nest maintainers are gone, then since the new ones will come from inside the nest, then naturally, the repaired nest will be smaller (?)

Positive feedback

- When successful foragers come in with food, then foragers within the nest, smelling both the foragers and the food, are stimulated to leave in greater numbers.

Limits

- There are so many foragers that can go out.

Negative feedback

- An increase in the interaction rate can lead to avoidance of contact, slowing or dispersing the accelerating intensity of response.

Weighted additive strategy

- Choosing nest sites in the lab with various combinations of illumination, cavity height, entrance.

Quorum sensing

- An ant leads other ants to a potential nest site it has found. When the number of ants is large enough, then they shift modes and simply carry other ants there, as it is three times faster for them to carry ants rather than to lead them. Nigel Franks.

Ant Relationships

Recognizing another ant as a nestmate

- Gordon: New ants accept all ants as friendly but as they grow older and shift out of the nest they start to recognize ants from other colonies as strangers. Based on the grease they are covered with.

Recognizing the task of another ant

- The smell of the ant covering grease makes evident the task that the ant does. The smell of the ant comes from the environment the ant has been in.

Rate of interactions with other ants (of various kinds)

- The ant gets an understanding of context from the rate of interactions with ants of different kinds.

- The same algorithm (and thresholds) will function differently in small and large colonies.

Coming back to the nest

- If a patroller avoids its trail, then it takes a long route back and finds its way by interactions with other ants it meets along the way.

Information buffer

- Lazy (taskless) ants still participate in the rate of interactions, which impacts the overall information flow. Dampen interaction and keep the system more stable.

Individual Ant Intelligence

Measuring area of a potential nest site

- An ant walks all around the nest site for a specified time, then goes out, reenters and registers the density of its own chemical paths. Nigel Franks.

Interaction of navigational modules

- Wystrach: Evolution has equipped ants with a distributed system of specialised modules interacting together. These results demonstrate that the navigational intelligence of ants is not in an ability to build a unified representation of the world, but in the way different strategies cleverly interact to produce robust navigation.

- Wystrach: Counter-intuitively, years of bottom-up research has revealed that ants do not integrate all this information into a unified representation of the world, a so-called cognitive map. Instead they possess different and distinct modules dedicated to different navigational tasks. These combine to allow navigation.

Modulation

- Ant’s navigational modules are not purely isolated. In the case of backtracking for instance, the experience of familiar visual scenery modulates the use of sky compass information.

Imagine path to home

- Wystrach: One module keeps track of distance and direction travelled, and continually updates an estimate of the best “bee-line” home.

Recognize visual cues

- Wystrach: A second module, dedicated to the learning of visual scenery, allows ants to recognise and navigate rapidly along important routes as defined by familiar visual cues.

Systematic search pattern

- Ants possess an emergency plan for when both of these systems fail to indicate what to do: in other words, when the ant is lost. In this case, they display a systematic search pattern.

Recent Experience

- Thus we have evidence that ants can also take into account what they have recently experienced in order to modulate their behavior.

Backtracking (Acknowledge ignorance or mistake)

- Wystrach: We showed that ants keep track of the direction they have just been travelling, allowing them to backtrack if they unexpectedly move from familiar to unfamiliar surroundings. ... Ants display this backtracking behavior only if they had seen their nest’s surroundings immediately prior to getting lost. This ensures that backtracking happens only when the ant is likely to be beyond the nest, rather than short of it.

Smell

- Ant relies on smell as it is basically blind.

Environment

- Ant figures out its environment

Stupidity

- Individual ants are very stupid. They are blind. They have no sense of danger. They typically meander. They do not deliberate. Perhaps they simply make efforts and at a certain point give up.

Altering

- Soldier ants can drum their bodies against walls to alert other ants.

Splitting a colony

- In some species, when a new queen is born, the colony splits in two, with half of the ants migrating along with the new queen and her brood. How do the ants decide to stay or go?

Supercolony

Global megacolony

Sources of Information

Thank you, Daniel, for your suggestions!

- Synthese. 2021 Feb;198(2):1457-80.

- Deborah M Gordon. An ant colony has memories that its individual members don’t have.

Deborah M. Gordon. Ant Encounters: Interaction Networks and Colony Behavior.

Deborah M. Gordon. Ant Encounters: Interaction Networks and Colony Behavior.

Deborah Gordon: How Ant Colonies Get Things Done. (Google Talk)

Deborah Gordon: How Ant Colonies Get Things Done. (Google Talk)

Deborah Gordon: The emergent genius of ant colonies. (Ted Talk)

Deborah Gordon: The emergent genius of ant colonies. (Ted Talk)

- Antoine Wystrach. We've Been Looking at Ant Intelligence the Wrong Way

Edward Wilson. Tales from the Ant World.

Edward Wilson. Tales from the Ant World.

- Feinerman, Korman. Individual versus collective cognition in social insects.

- Deborah Gordon. Wittgenstein and Ant-Watching.

Daniel Friedman. Bucky, Wittgenstein, Ants.

Daniel Friedman. Bucky, Wittgenstein, Ants.

- Sonoran Desert Ants

- BBC Video: Empire of the Desert Ants. 2011. Arizona. Honeypot ant (Myrmecocystus mimicus). Bert Hölldobler of Arizona State University, collaborator of E.O.Wilson

The Largest Civilization in the World

The Largest Civilization in the World

Nigel Franks. Ants, Bees and Brains.

Nigel Franks. Ants, Bees and Brains.

- M. Lanan. Spatiotemporal resource distribution and foraging strategies of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). 2014.

- https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/full/10.1086/693418

- https://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/article?id=10.1371/journal.pbio.1001805

- https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev-neuro-070815-013927

- https://www.mdpi.com/1099-4300/25/7/964

- The genomic architecture and molecular evolution of ant odorant receptors (2018)

- Michael Levin. The Computational Boundary of a “Self”: Developmental Bioelectricity Drives Multicellularity and Scale-Free Cognition.

A discussion between John Vervaeke, Gregg Henriques, Justin McSweeny, and Mike Levin.

A discussion between John Vervaeke, Gregg Henriques, Justin McSweeny, and Mike Levin.

- http://pespmc1.vub.ac.be/Papers/Stigmergy-Springer.pdf

- Ants learn fast and do not forget: associative olfactory learning, memory and extinction in Formica fusca

- Desert ants possess distinct memories for food and nest odors

- Long-term memory of individual identity in ant queens

- https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0018491

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gamergate_(ant)

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/queen-pheromones#:

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32305342/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tinbergen%27s_four_questions

- Kapheim. Synthesis of Tinbergen’s four questions and the future of sociogenomics. 2018.

- https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1iPIBjEAghkRjnD6qZw0y1ssRcvwo382uYt00gJPy9Ww/edit?usp=sharing

- https://www.mdpi.com/1099-4300/25/7/964

- A snapshot and pipeline for tissue-specific gene expression meta-analysis in honey bees (Apis mellifera)

- Martin Fortier, Daniel A. Friedman. An interview with Karl Friston. Of woodlice and men: A Bayesian account of cognition, life and consciousness.

Yannick Wurm. How do genes make an ant society?

Yannick Wurm. How do genes make an ant society?

I would ask to learn about the tra trajectory that led ants to translate simple patterns of encounter into decisions about what to do next. This is what produced the organization of the colonies we see today.

But some colonies forage every day, no matter what. Others seem much more finicky, foraging only on some days and sending out few foragers one day and many the next.

Consciousness is in the nest maintainers and the memory buffer. They choose whether to alter interaction rate or grooming semiosis. They control by building the nest, by moving the breed and the queen, by architecting and restructuring the "brain"

Colonies may vary in the magnitude of the increase or decrease in the rate at which foragers return needed to trigger a response. Then in one colony, the inactive foragers would respond to a small difference from the baseline in their rate of encounter with returning foragers, while in another colony, it would require a larger change to jolt the foragers from their standard waiting time. Overall, the more sensitive colony will adjust its foraging behavior more often.

Any model of ant behavior has to have at least two levels. The first specifies how the workers interact within the colony to regulate the acquisition, processing, and distribution of resources. The second specifies how the internal processes of the colony connect to the colony’s environment. The colony’s behavior influences colony growth, and how colony growth affects all the other organisms that the colony uses and interacts with, which in turn will feed back on the colony’s ability to grow. Although the first level is sometimes called ‘behavior’ and the second ‘ecology,’ they are clearly inseparable

A series of studies by Franks, Pratt, and others on nest moving in Temnothorax, discussed in chapter 3, explains how 60 to 75% of colonies choose their nests.1 But about 25% of the colonies always do something different. Why?

Separation from larvae generates stress.

The success of a new nest, a new colony is a very delicate matter, and thus may be the focus of consciousness, to send off the new colony at the best possible time and to the best possible site.

The health of the queen can also be a source of concern.

Daniel's summary of Karl Friston's thoughts on ant colony consciousness, Of Woodlice and Men

- Consciousness is a process. A process of inference.

- Variational Free Energy = Bayesian Evidence Maximization = Surprise Minimization = ...

- See Active Inference Textbook equations 2.5 & 2.6 for more information.

- Minimal selfhood:

- Counterfactual breadth

- Temporal depth

- Generative models with predictions about consequences of action.

- Generative models distinguishing Self and Other.

- Generative models distinguishing Others of different kinds/grades of similarities and differences.

- Biology

- Ant semiotics - remove noise like quantum computing. Noise-free environment (isolated subsystem) is the quantum world.

- Daniel Ari Friedman https://cognitivesecurity.us